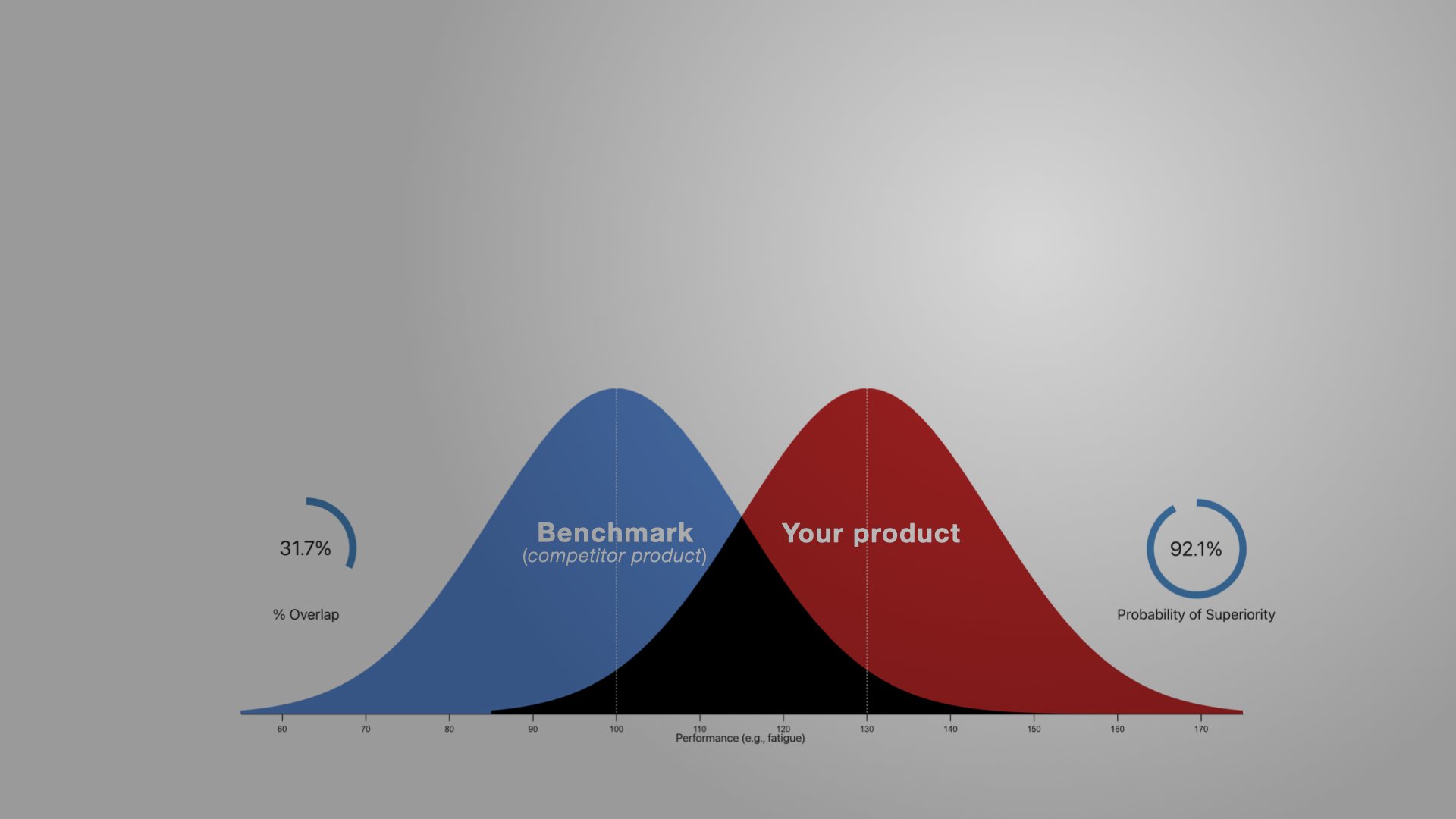

Prove The Value Of Your Design With Effect Studies

Your potential customers will only buy your product if they believe in the value that it can give them.

While it is easy to claim the value - it is much harder to back it up with data.

For a customer to buy your product, they need to know and believe in the value that you claim it will bring them.

It is, however, easy to claim that you are providing great value - but much harder to make data-driven claims. Further, data-driven claims can differentiate you from your competitors who often offer similar claims, and thereby make your claims more believable to the customers.

We often see undifferentiated and unsubstantiated claims whenever it comes to “user-friendly design”. Everybody is claiming ‘intuitive’ and ‘user-friendly’ design, but only a few actually back this up with data. Even more rarely, we are informed what the business value of those qualities is.

We believe this is an opportunity for companies who want to stick out from the crowd by backing up their claims with data and clearly outlining what the value is.

But how do you do this?

The answer is effect studies.

What Is An Effect Study?

Any company should be able to specifically and precisely describe the value of their design for their customers. But to make your claims believable and unique, you need to back them up with data.

The tool for this is effect studies.

An effect study is a method that documents your product's (superior) qualities.

While technical claims about a products's specifications are easy to look up (e.g. mega-pixels on camera or memory on a computer), we cannot in the same way look up claims related to the quality in use of a product.

Such claims instead need to be documented in an effect study where we sample data on how the product performs in the hands of real users in real use situations.

Three examples of "quality in use" claims

• “It’s easy to use (requires little to no training).”

• “Using our product gives you more motivated employees.”

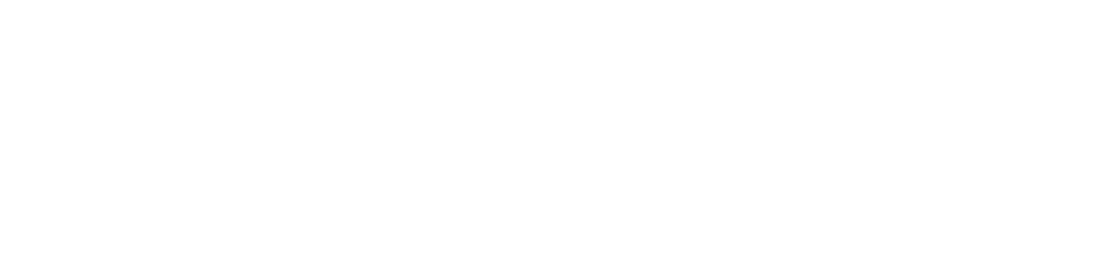

• “Our design makes the user less fatigued.”

Effect studies are methodologically similar to scientific experiments and clinical trials: we carefully design a measurement and study approach that can isolate and document a particular product or design's effect on the outcome we want to make claims about.

Below we will outline how you can work with quality-in-use effect studies as a strategic differentiator and how to get the largest possible impact from doing it, to help drive sales and dominate the market.

Let us start with an overview using our “X-Factor” model.

The X-factor: How To Get Stronger Claims With Effect Studies

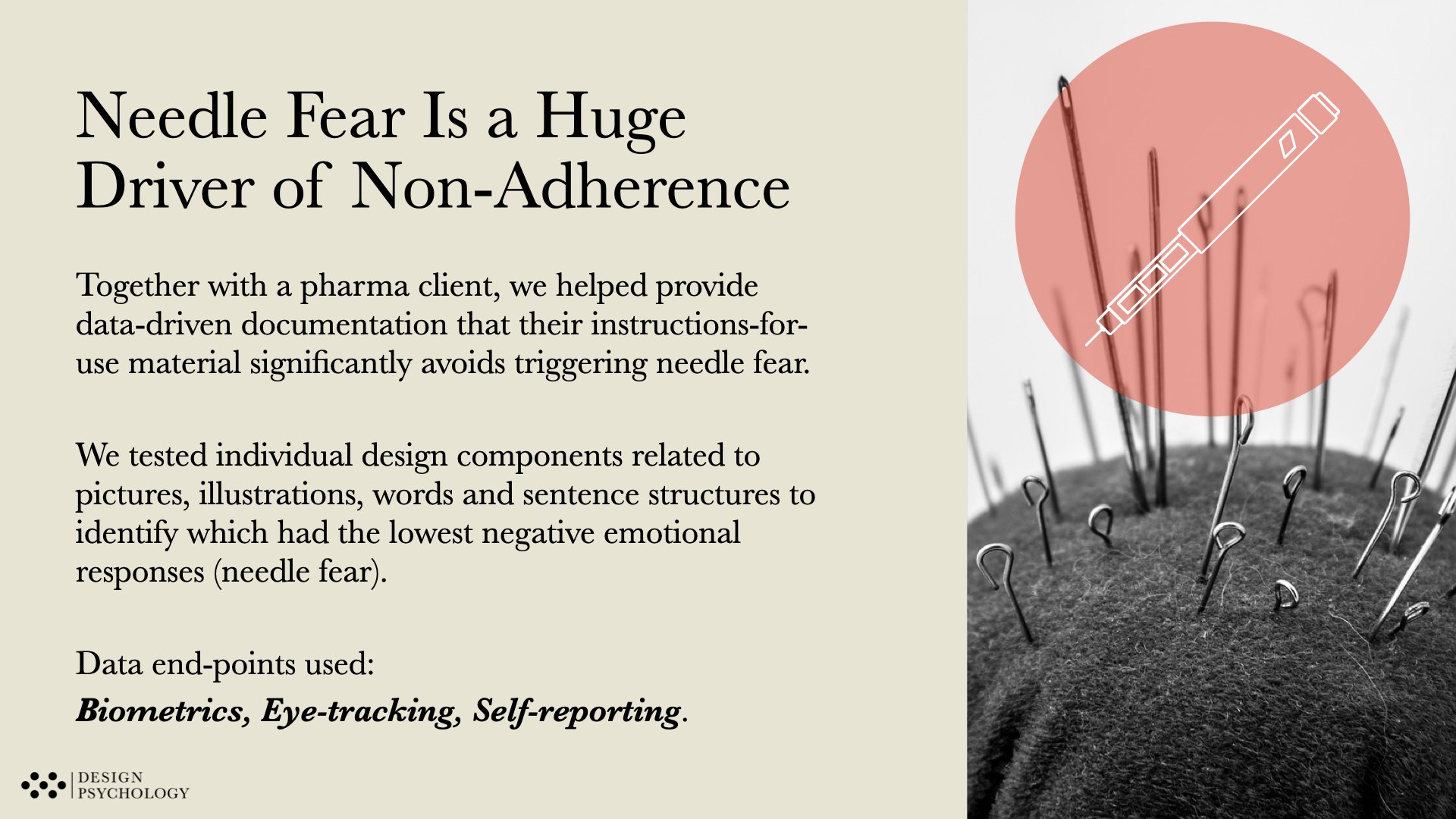

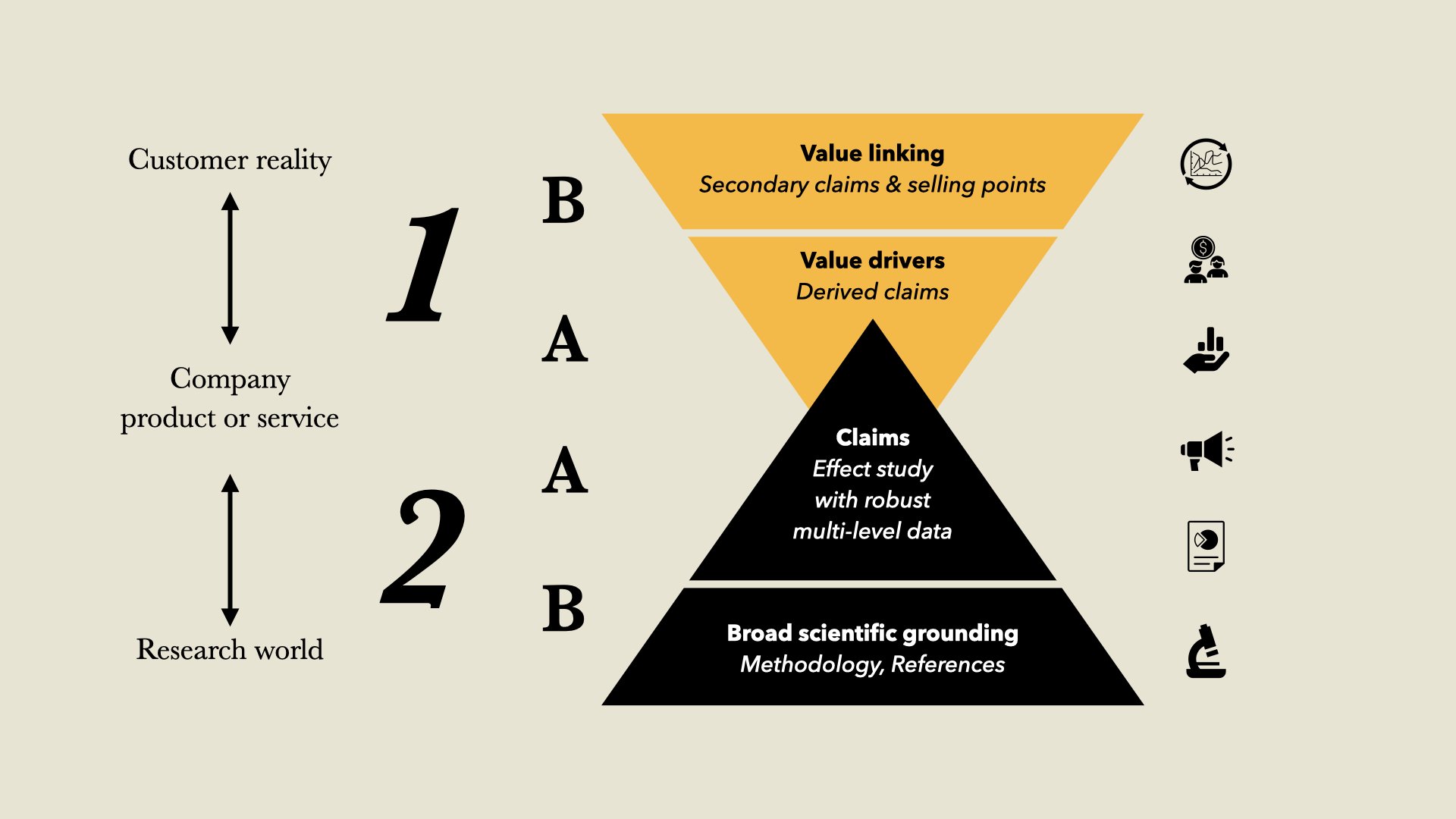

For an effect study to support strong claims about the value of a design, we need to do two things:

First, we need to link the value of the data from the effect study to how this is relevant (often in multiple ways) to the customer. We refer to this as value drivers and value linking.

Second, we need our claims to be as powerful as possible. We do this by backing up the claims with a robust study design linking the effect study to the existing foundation of scientific research.

These two broad considerations make up the X-factor model:

The point of the X-factor is that for a data-backed claim to stand strong, we need to ground it on both ends of the X: The customer reality at the top and the scientific and methodological grounding at the bottom.

Let us unpack each of these two steps of X-factor:

Step 1:

Linking Claims to The Customer Reality

The first step in doing an effect study is to explore whether the effects we might be able to claim with data might resonate with our target audience(s). That is, determining whether the business case for an effect study is sufficiently strong.

An effect study can cost 20.000 to 60.000 € and therefore requires a solid business case in order to be a viable pursuit.

We analyse the business case by looking at the value of the claims we might back up with a study and how they impact the customer.

We do this in two ways:

A) Value Drivers, and B) Value Linking.

A) Value Drivers - the immediate impact

Take, for example, a company that provides a product that wants to claim it can reduce workplace fatigue. While an individual employee can easily appreciate the value of reduced fatigue, we need to explore how that directly impacts the workplace. What is the value of reduced fatigue for the workplace that invests in the product? That claim is valuable to the individual employee, but what does the workplace gain?

Research suggest that no less than four hours per week are lost in productivity to fatigue; we now have a value driver: reducing lost productivity. That reduction in lost time is a “business currency” that easily plugs into an excel sheet and business analysis at most companies.

By thinking one step further from fatigue to what is the effect of fatigue reduction in the customer reality, we increase the strength of the selling point.

The critical question is, then - why don’t we simply measure lost productivity instead of fatigue? …messy reality…. one data point. Fatigue has a broad range of value drivers. Rather than measure each an one of those we can corroborate…

Similarly, a new MedTech device that promises to be more ‘intuitive’ or ‘user-friendly’ could have a stronger value proposition if that can be linked to derived values, such as:

Decreased training costs,

More efficient use of the device or;

Less device downtime because of better or more timely maintenance.

In this way, we describe how the claims about our design provide real, tangible value for our customers.

B) Value Linking - the derived impact

If we want further to extend the business case and value proposition of a design we use value linking.

With value linking, we look at the ripple effects of your design's value on people, processes and businesses, which are secondary effects, but still valuable to the customer. Here is an example:

Consider a new solution that allows burn wounds to be treated bedside by nurses instead of in an operating room by surgeons.

That is valuable, not just in that it saves expensive resources, but also in linked effects, that the hospital can staff up with more accessible and cheaper personnel.

Also, patients can have family next to them to alleviate the traumatic impact of a burn wound.

The better you understand your end users, the better you can map out and link to the total value of your product. That makes the value clearer and gives you the best foundation for deciding on whether you should invest in an effect study.

Step 2: Developing A Robust Study Design

We need a robust foundation to back up the attractive claims we’ve identified in step 1.

That foundation consists of two strategies:

A) Robust methodology and B) Scientific Grounding.

A) Making Sure Your Effect Study Has A Robust Methodology

A well-designed effect study ensures you get robust and nuanced data that directly supports the claim types you want to make relative to the desired value drivers and value linking.

To do this, the study design and methodology must be as scientifically valid as possible. If we do not do this, it risks undermining the validity of an effect study if the method is weak.

For example, suppose we want to claim that a product reduces fatigue and will improve productivity because productivity and fatigue are linked in the scientific literature. In that case, we need to ensure that we are measuring the same type of fatigue that drives non-productive time.

Whenever possible, we should avoid making up our own “measurement stick” but instead rely on what we already know about measuring something like ‘fatigue’. That is an excellent way of ensuring that we are measuring what we claim to measure, and that we can link our data with other supporting findings.

B) Scientific grounding

After we have developed a robust methodology for an effect study, we can power the results we find from the study by ensuring that it is well-connected to existing research approaches and knowledge.

By linking up with existing research, we use reference data and findings beyond our effect study that can bolster our claims. At this moment, the specific data of the effect study can be compared to previous findings to help contextualise our results. For instance, is the effect that we find substantial?

While the effect study aims to generate data that can support claims, we can harness “claim power” from the findings in other studies by ensuring we build our study on top of the existing scientific foundation - not next to it.

The complete X-factor model with an example

Below you find the overview of the full X-factor model.

The second slide depicts an example of the four layers from deep science to derived value linking effects.

After the steps above, marketing needs to build a narrative that makes the most out of the data your effect study has provided you for your claims. With the X-Factor grounding of your effect study, you should have the most robust and comprehensive foundation for doing this.

Four ways to learn more:

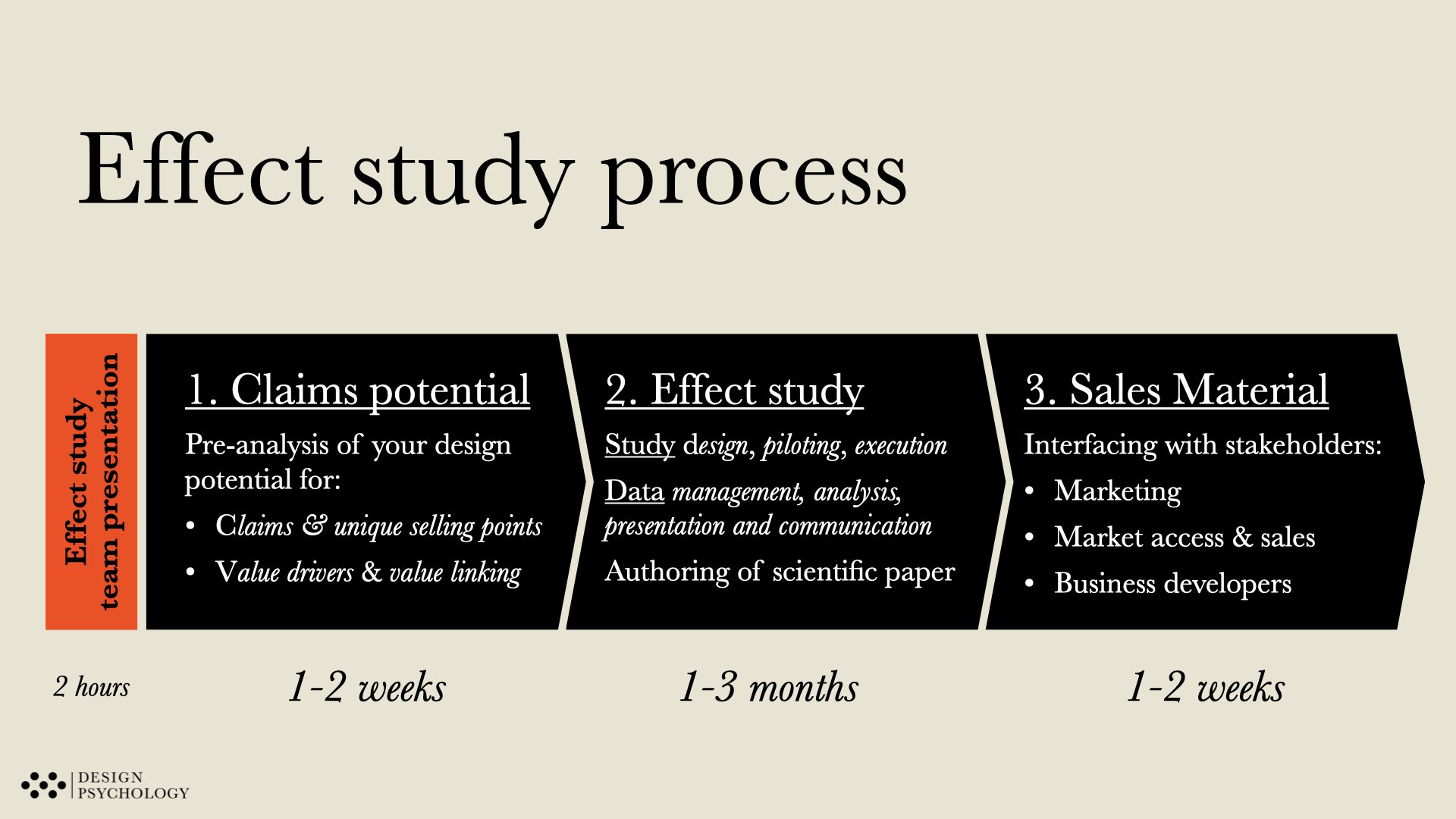

A: Let us help identify your x-factor potential

The first step you can take is to onboard your team to the business value effect studies can produce for your organisation in providing data-driven claims and unique selling points.

After this onboarding meeting, effect studies typically fall into three phases, as depicted below. Each phase is tailormade to your organisation to ensure the right involvement of internal stakeholders and resources (e.g., R&D, front-end user research, design development, project leads).

Do you want to find out if an effect study makes sense for your product claims?

Then feel free to call us on +45 4041 4422 or book us for a free presentation on how to get started.

B: Learn to work with the X-factor model yourself

Attend our 3-day course in Strategic UX Design to learn about the entire process behind UX claims, from UX-driven value propositions to UX requirements to Data-driven UX claims.

C: Read our article about UX claims

Steer away from your competitors. Add UX claims to your unique selling points.

This is about to change drastically.

The question is - will your company take the lead in providing data-driven UX claims?

Link: www.designpsykologi.dk/claim-to-fame-with-ux-claims